Contact: Crystal Drake, Office of Communications, Public Relations and Marketing

“Teaching people to fly had his heart” says his son, Charles Anderson, Jr.

“It would have been Dad’s greatest dream,” said his son Charles Alfred Anderson, Jr. when asked what his father might think about the rebirth of the aviation science program at Tuskegee University which will produce its first graduates in May 2026. “I know he’s cheering it on.”

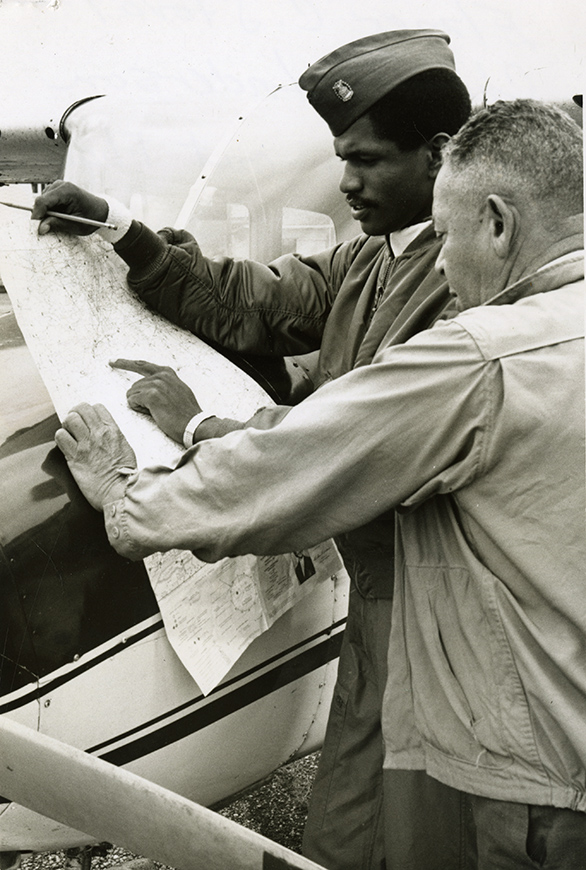

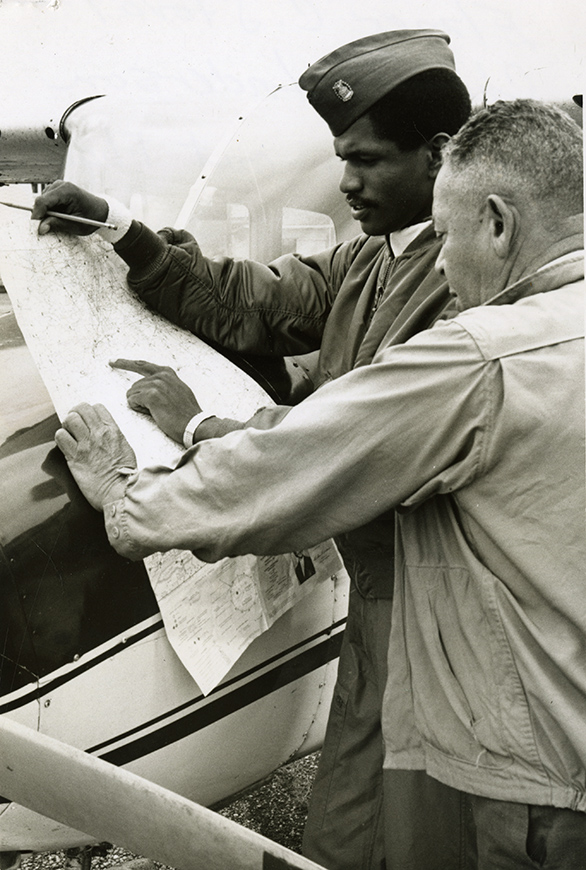

Known by many as the “Father of Black Aviation,” Anderson trained the young men who went on to make history as the storied Tuskegee Airmen. Anderson remained an important part of Tuskegee’s aviation legacy as a flight instructor in Tuskegee’s ROTC program through the 1970s, training hundreds of pilots that went on to aviation careers in the military, including World War II, the Korean War, and Vietnam, as well as with commercial airlines and as instructors themselves. He continued to fly, instruct students and mentor many until 1989.

One such student, Colonel Palmer Sullins, remembers Anderson as a father figure. “He was so unassuming, but he was a giant in my eyes,” said Col. Sullins, a Tuskegee alumnus and U.S. Army veteran, who trained under Anderson in the ROTC program in the early 60s. Col. Sullins is a long-time civic leader, an accomplished pilot, and chairman of the Friends of Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site. He and Charles Anderson, Jr. became close and now refer to each other as brothers.

It was “Chief” Anderson who piloted the plane in April 1941, giving First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt first-hand experience of the aviation prowess being developed in Tuskegee. It was a skill many believed, because of racist ideology, was impossible for Black people to master. Only after this visit were the Tuskegee Airmen commissioned to fight for their country as the first African American fighter squadron in the U.S. Army.

When Tuskegee Institute won the government contract to establish a Civilian Pilot Training program, the university sought Anderson to become the chief flight instructor. His students began calling him “Chief” with respect and affection, a moniker that stayed with him for the rest of his life.

By June 1941, Anderson was selected by the Army as Tuskegee's Ground Commander and Chief Instructor for aviation cadets of the 99th Pursuit Squadron, America's first all-black fighter squadron. The 99th would eventually join three other squadrons of Tuskegee Airmen in the 332nd Fighter Group, known as the Red Tails. The 450 Tuskegee Airmen who saw combat flew 1,378 combat missions, destroyed 260 enemy planes, and earned over 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses, among numerous other awards.

Anderson was already an accomplished aviator when he was recruited by Tuskegee. The first African American to earn a commercial pilot’s license in the U.S., he was denied formal flight training due to segregation, but with the support of others taught himself to fly, earning his pilot’s license in 1929. In 1932, he became the first African American to earn an air transport pilot license from the Civil Aeronautics Administration.

Anderson and his partner Dr. Albert Forsythe made a record-setting transcontinental flight from Atlantic City, New Jersey to Los Angeles, California. In the summer of 1934, they flew their plane, christened “The Spirit Booker T. Washington,” on a good will tour through the Caribbean to the Northeastern tip of South America, becoming the first pilots ever to land a land-based plane on the island of Bahamas.

“There are generations of students that followed the Tuskegee Airmen, both military and civilian,” his son added. “And that is just as he would have wanted. He was a visionary, always looking forward.”

“Chief Anderson embodied the essence of mentorship – the selfless desire to bring others along, to lead by example and to do it from the heart,” said Dr. Mark A. Brown, president and CEO of Tuskegee University. “As our Aviation Science students take flight from Moton Field, the same field where Chief Anderson made history and returned for decades to train so many other aviators, his legacy lives on in them.”

© 2025 Tuskegee University

“It would have been Dad’s greatest dream,” said his son Charles Alfred Anderson, Jr. when asked what his father might think about the rebirth of the aviation science program at Tuskegee University which will produce its first graduates in May 2026. “I know he’s cheering it on.”

“It would have been Dad’s greatest dream,” said his son Charles Alfred Anderson, Jr. when asked what his father might think about the rebirth of the aviation science program at Tuskegee University which will produce its first graduates in May 2026. “I know he’s cheering it on.” It was “Chief” Anderson who piloted the plane in April 1941, giving First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt first-hand experience of the aviation prowess being developed in Tuskegee. It was a skill many believed, because of racist ideology, was impossible for Black people to master. Only after this visit were the Tuskegee Airmen commissioned to fight for their country as the first African American fighter squadron in the U.S. Army.

It was “Chief” Anderson who piloted the plane in April 1941, giving First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt first-hand experience of the aviation prowess being developed in Tuskegee. It was a skill many believed, because of racist ideology, was impossible for Black people to master. Only after this visit were the Tuskegee Airmen commissioned to fight for their country as the first African American fighter squadron in the U.S. Army. Anderson was already an accomplished aviator when he was recruited by Tuskegee. The first African American to earn a commercial pilot’s license in the U.S., he was denied formal flight training due to segregation, but with the support of others taught himself to fly, earning his pilot’s license in 1929. In 1932, he became the first African American to earn an air transport pilot license from the Civil Aeronautics Administration.

Anderson was already an accomplished aviator when he was recruited by Tuskegee. The first African American to earn a commercial pilot’s license in the U.S., he was denied formal flight training due to segregation, but with the support of others taught himself to fly, earning his pilot’s license in 1929. In 1932, he became the first African American to earn an air transport pilot license from the Civil Aeronautics Administration.